Examination of Baggage

prior to sailing to Byzantium, or thereabouts.

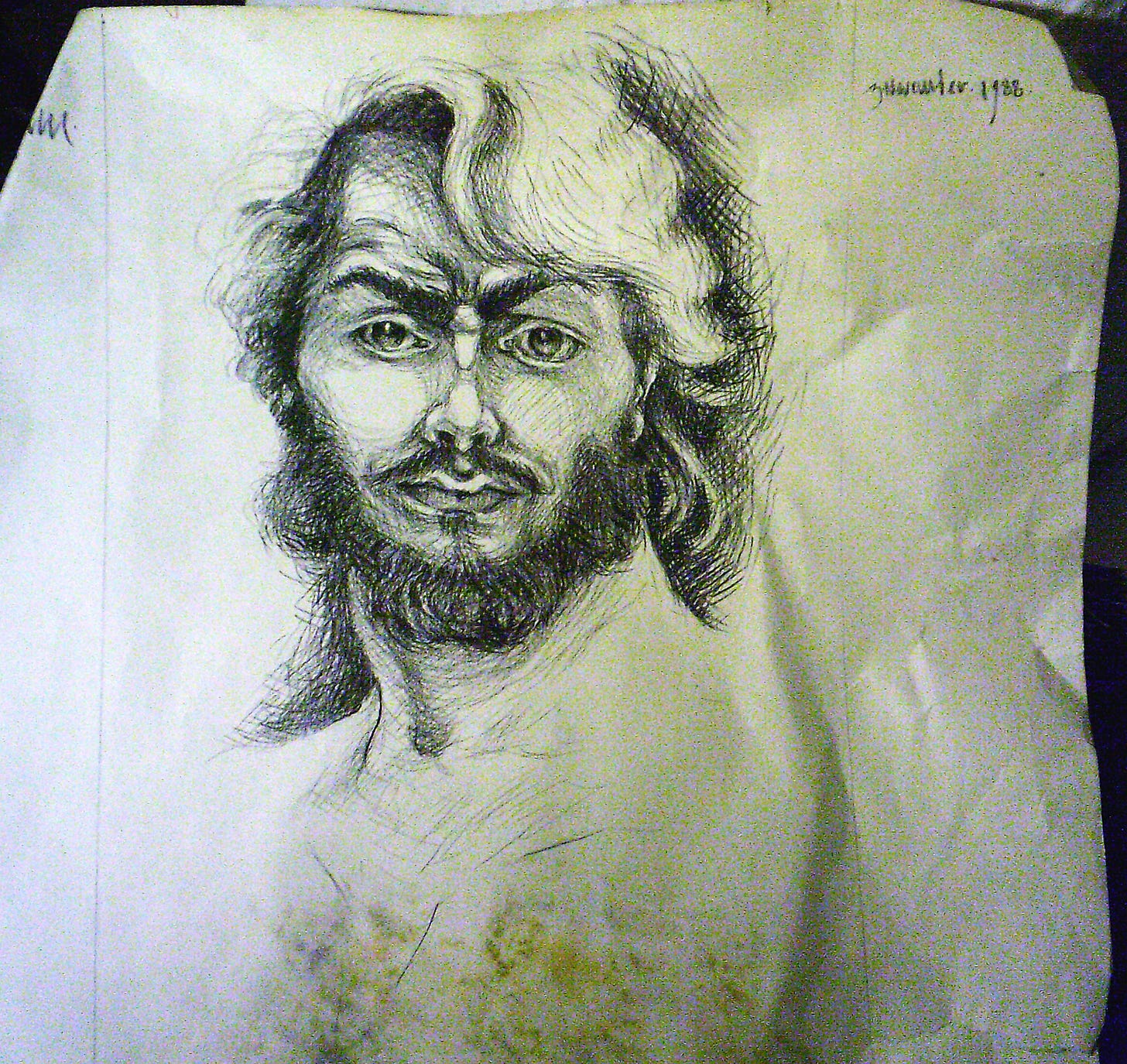

Sketch, Self-Portrait, 3 November 1988; graphite on drawing paper with stains from motor oil and storage in a car trunk in the 1990s; about 30” x 36”

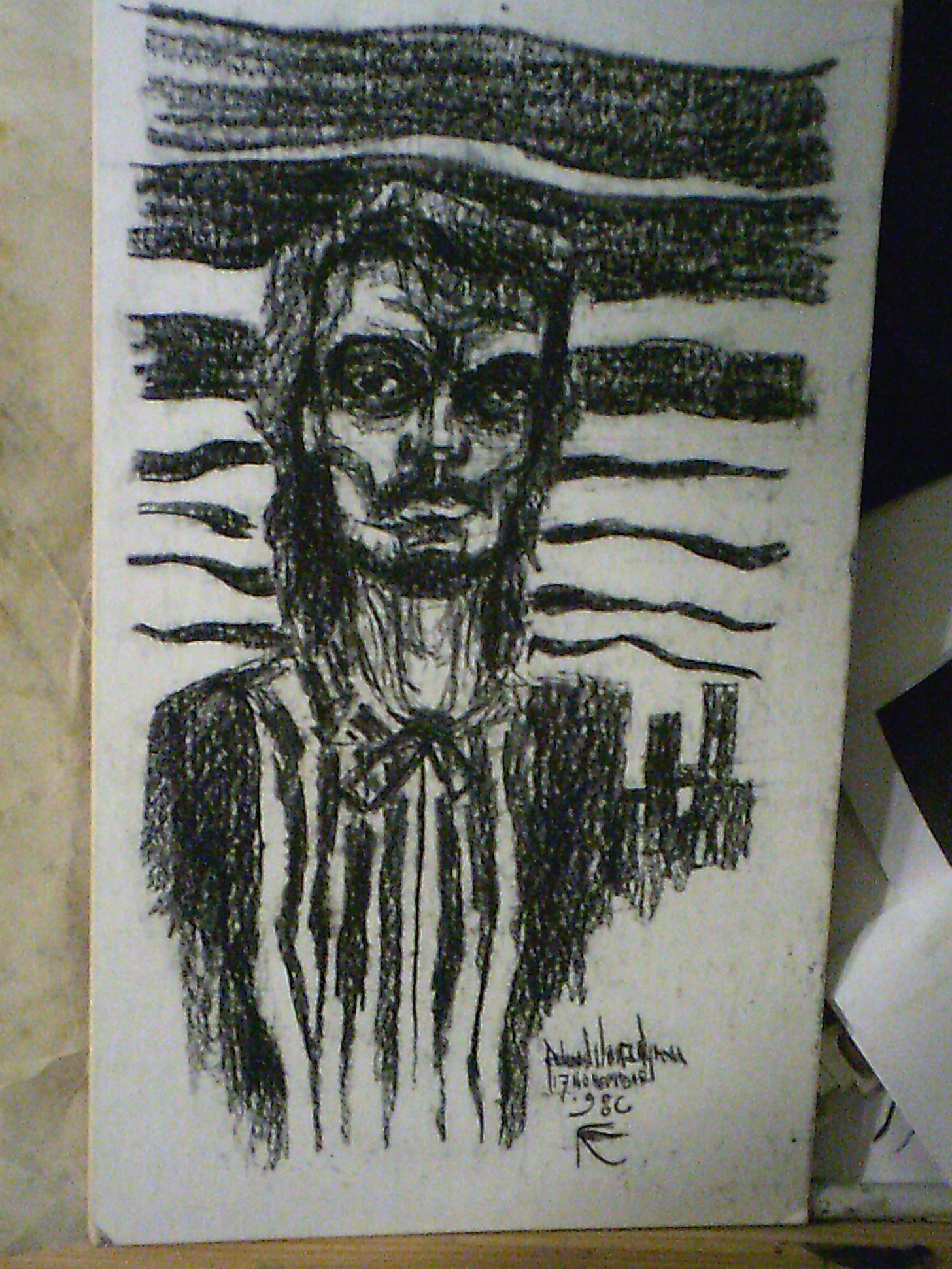

Sketch for a woodcut never made; self-portrait, unfixed, smudged charcoal on the back of a piece of mat board; 17 November 1986; about 7”x 12”

“Tired of lying in the sunshine

Staying home to watch the rain

You are young and life is long

And there is time to kill today

And then one day you find

Ten years have got behind you

No one told you when to run

You missed the starting gun”

from TIME

Pink Floyd

DARK SIDE OF THE MOON (1973)

I.

Ten years old.

I was ten years old, I think, when I scraped up the cash to buy this Pink Floyd album. May have been 9 — it doesn’t matter; a young guy just done with high school who worked in the machine shop at my old man’s auto parts store played it for me out in the parking lot on his 8-Track. The guy bought it to test the stereo on his car, a hand-built hot rod with custom sound. My mind was, as folks said back then, blown.

Not by the car or stereo — the music. Oh my G-d. It sounded like nothing else I heard on the radio; mesmerized, I sat there slack-jawed. The guy let me remain frozen in the passenger seat and listen to the whole thing while he fooled with his car — a great mercy shown to a kid.

My mania became the acquisition of that album on vinyl, of course, so I could play it on a monophonic piece of plastic junk that passed for a record player. And so it was, after a few months of scraping dimes and quarters and conning my sister out of $3.00 from her allowance (a thing I did not receive - a different story there). Over and over, my ears listening to everything, anything I could pick up from that album, all the mysterious lyrics, sounds, explosions in “On the Run,” the loose narrative I made up to explain the way these songs and titles hung together like a novel written in sound. The exhilarating mental images from the thing that haunted me day to day.

Until one day in particular — and I was 10 years old that day — when I stopped listening to the sound of the words and heard the apocalyptic meaning in that line:

”And then one day you find

Ten years have got behind you

No one told you when to run

You missed the starting gun”

Wait! Ten years were behind me… and no one ever told me I was in any sort of race at all. A race with the sun… a race with time… a race against mortality. A race which no one wins if they conceive of life as a game or series of destinations at which one must arrive — destinations of utility chosen for you by culture, religion, community, school whether you really understand why or not.

Why, why am I supposed to run a race I cannot win? Is that sort of meaningless futility what life is actually about? Is that all there is?

Is that the nature of all this: a Great Cosmic Rip Off?

That latter bit would take me decades to work out for myself, thinking about and studying religions and philosophy; but there it was, screaming in my ears, a chorus of mad prophets and guitars and I, only 10, no one to even attempt to share this revelation with or to discuss the horror that arose within me and never really left.

The gravity of realities such as loss and mortality never decreases, whether one pays attention to them or not. Those human themes and the ideas about them only grew within my life because I turned out to be that sort of person. The sort of person who wrestles with such themes, such ideas, such realities regardless of the potential uselessness of the activity.

Over time, I came to grasp that there is a chasm between “usefulness” and “value.” All things of value are not useful in the least; and all things that may seem useful may be entirely devoid of human value and meaning. In fact, they may be antithetical to human values and needs.

So, if by the utilitarian standard my life amounts to losing, failing to arrive at those predetermined stations measuring “success,” at this point I could not care less.

I don’t believe that’s the point of the time we’re granted.

II.

”Welcome my son

Welcome to the machine

What did you dream?

It's all right, we told you what to dream

You dreamed of a big star

He played a mean guitar

He always ate in the Steak Bar

He loved to drive in his Jaguar

”So welcome to the machine”

from WELCOME TO THE MACHINE

Pink Floyd

WISH YOU WERE HERE (1975)

1977 — that was the year I laid hands on Wish You Were Here. Didn’t have to pick up soda bottles and exchange them for dimes to get it, either, or talk some kid out of spare change. No, my father bought it for me at Gibson’s Department Store after I’d spent the better part of a summer going in there and examining the mysterious cover and after a couple of years hearing “Welcome to the Machine” and “Have a Cigar” on the radio.

It wasn’t my birthday. Nothing of the sort was associated with the gift — a rarity where my father was concerned, especially when music was involved. In fact, I can’t recall my old man ever buying me another album.

There was, I think, a reason or a meaning involved in the purchase: depression, his own and mine.

I was 11 years old in 1977.1 I’ll keep this brief because it’s more background information to what I’m exploring than the subject itself: In 1977, my mother took my sister to spend the summer in South Georgia with my aunt and her parents. Then, she simply refused to return. Before the end of that summer, her parents drove her up to Dahlonega, Georgia where we lived; they had a truck; my mother wore a ridiculous wig as a disguise but as they passed through town, someone spotted her and called my father at the auto parts store (it was a very small town; my father knew or was related to everyone) — he ran for his own truck and I followed. By the time we got there, sure enough, they were toting armloads of her clothing and my sister’s clothes out and dumping them in the truck.

My mother hadn’t spoken to me since she left, wouldn’t speak to me on the phone the few times my father got through. I still don’t know why. My mother stepped towards the back yard to smoke a cigarette and I followed, guts churning with fear and anxiety.

”Why did you leave me?” I asked. “Why didn’t you take me, too?”

She had, after all, taken my sister to the opposite end of the state; we didn’t know if the kid was dead or alive, to be honest, or at least I didn’t.

She took a slow drag on the cigarette and, without looking at me, said, “You wouldn’t have gone.”

”No, I wouldn’t have. Because this isn’t right, mom. You shouldn’t have done this.”

Emotionless, as far as I could tell, she finished her smoke, turned, and left. Cold in the late afternoon heat of August. I was shattered into a billion pieces internally along the wounds and emotional fractures built up over the previous years and months. And I had to suck it up, turn around, and go watch that truck pull out and head back south, my father’s head hanging silent, dejected. That’s the way it was going to be, him and me, for months.

I was told, repeatedly, that I wasn’t the reason she left. Never believed them — part of me still doesn’t believe it though, at age 10, 11, what magical power did I have over an adult to make them choose to do anything? That conclusion took years of therapy for me to be able to grasp. But some things haunt you for life, affect everything, whether you like it or you don’t, so you learn to live with or through it… or you don’t.

So, he bought me that Pink Floyd album because I asked for it. I didn’t ask for much as a kid and I asked with no faith he’d shell out for it. But he did, silently, and I proceeded to listen to it daily, repeatedly for awhile. By then, I’d acquired a cheap plastic stereo with two small speakers. I’d lie on my bed, one speaker over each ear, close my eyes and go… somewhere else. Hope I could imagine somewhere else to go one day. Some destination that would spell “success,” where I could be an artist, where I could be known for what I was good at and never have to deal with people who treated me with the same care one gives any other disposable object… and for no discernable reason.

[Yes, I know the album is a memorial to Syd Barrett, the founding member who, early on, went off one weekend and dropped a massive dose of LSD — his friends brought him back home… well, his body was brought home. He was gone, on a permanent bad trip. I’m unsure of the details; they don’t matter. The effect was: he couldn’t play music anymore, communicate effectively, live his life. The acid either kicked off schizophrenia, which he may have been prone to, or else the acid gave him the equivalent of “schizophrenia” with all the hallucinations, delusions, flat affect, and absence that implies. He was permanently psychotic.

So, Pink Floyd invited in David Gilmour who became the replacement for Barrett. Just in time for the band to hit the big time, the benefits — and absurd tribulations and realizations about fame — which Barrett never shared; but he was always remembered by his band mates: “Wish you were here.”

That album is about many things, but one major theme is loss, loss of their Icarus-like imaginative genius, their friend, their far-off crashed psychonaut. Shine on, you crazy diamond.]

However, I was 11 years old living in Southern Appalachia and didn’t know too much about Syd Barrett at that time. I didn’t know much about Pink Floyd’s backstory — I just knew the music and eventually worked at decoding the lyrics which, like many other people, sometimes I found personally meaningful, more so as I aged when fortunate.

So, I listened obsessively to this beautiful album about loss while I, too, experienced a terrifying sort of loss, a loss of the illusion of stability, the illusion of care, the illusion of my own importance, the illusion I was part of a family, the illusion my mother even liked, much less loved, me. What in the hell was “love” if it could be abandoned as casually as my own mother abandoned me?

Who in this world was I to talk to about this? My father was on the edge of a nervous break down — I could not lose him and that meant I could not become any more of a burden than I already was. Since age 10 I’d already looked out for myself as much as possible — I realized adults were not paying attention, so I started slipping through those cracks in the attention, going to the college library after school, reading and exploring whatever I wanted, hanging out in abandoned houses owned by relatives.

At age 11 I simply stepped this up. I picked up Coke bottles for cash, bought comic books, magazines, paperbacks, hit the college library, bought candy and hamburgers for food, saved up lunch money for larger purchases. I sucked everything up, crammed it all down, showed as little emotion as possible.

If I was picked on, I didn’t fight — that would cause someone to call my old man; he didn’t need the stress. So I took it and all the names that went with not pounding the shit out some punk who had it coming, just silently walking away. And I didn’t rat — that just stirred up more trouble; if I couldn’t handle something myself, I let it ride.

Best adults, especially at school, not become involved in my business because then, they might find out what was going on at home. G-d knows what, if anything, would follow. My imagination said: Nothing good.

Welcome to the machine.

I could de-code or “read” what happened in that song eventually. A rock star — perhaps the ones singing the song, eh? Inside knowledge and lamentations — moves in his memory from the pure, raw intentions of youth:

”Welcome my son

Welcome to the machine

Where have you been?

It's all right, we know where you've been

You've been in the pipeline filling in time

Provided with toys and scouting for boys

You bought a guitar to punish your ma

You didn't like school and you know you're nobody's fool”

Note, however, his memory is being mediated, fed back to him and narrated, by… something else. The personification of the music industry, capitalism, that exchanges the once rebellious nature of rock’s creativity: “You bought a guitar to punish your ma/ You didn't like school and you know you're nobody's fool” for all the cash created by fame for the recording industry. It turns art into business at the price of grinding down the artist and true creativity… and substituting the real dream of art for some predetermined “stations” marking a false success, such as I spoke of earlier:

”Welcome my son

Welcome to the machine

What did you dream?

It's all right, we told you what to dream

You dreamed of a big star

He played a mean guitar

He always ate in the Steak Bar

He loved to drive in his Jaguar

”So welcome to the machine”

There it is, the dreams we created for you to buy: You are a big star; you play guitar before adoring fans; you eat at the Steak Bar and drive your Jag.

All it cost was your soul. And you know it by the end of the song.

The final noise as the music fades on this song sounds like an elevator… perhaps going down, metaphorically. Delivering the rock’n’roller to yet another obligatory music industry function, a party, maybe at an album premier in a room full of critics and hangers on who have no clue about the internal life of the human that elevator just delivered into this metaphorical hell.

Wherever the place he’s going is, it isn’t where he wanted to go… but what will he do? Get his soul back and run out, live an impoverished life now, playing for honest reasons but working… where? As a mechanic? A janitor? A teacher? Just what the hell is he qualified to do for money at this point?

One can smell how anxiety and despair might start whispering death would be an exit, a clean getaway.

Music industry fame was a trap and Pink Floyd were in it. Welcome to the machine.

Was it better Syd Barrett missed this part of things in the manner he avoided it? Neither seem good alternatives at all.

I don’t know. I wasn’t Syd Barrett, but I was an 11 year old nobody, horrified at the idea of being trapped in a foster home, a boy’s ranch, juvenile detention. I was depressed, clinically depressed, something I wouldn’t be diagnosed with until the school psychologist told me in 12th grade. My mother was not exactly sane all of the time and she was prone to verbal, physical, and psychological violence — G-d forbid I wind up like her or other relatives I watched deteriorate over the years. My father’s own pent up anger and fear would began erupting, so I lost even him. My sister and I, not really raised together or in the same way, five years between us, was more like a distant cousin. I felt alone.

I was alone.

I did my best to remain more or less alone, even in the company of friends, when I made a few. The less attention I drew to myself, the better. If I wasn’t invisible, I did my best to be unnoticed, to come and go quietly… because I wanted to be an artist and a writer, to do creative work, maybe teach college to make a living, and get as far away from this nightmare as possible.

Nightmares, however, are internal. They travel until you talk to them, face them, live in them, live with them. And the way I crammed down the memory of events, the feelings about them, and kept them hidden inside eventually cost me dearly. Decades would pass before I even vaguely grasped that could be an outcome.2

III.

Look at the top at the two “self-portraits,” the one from 1986 and the one from 1988.

Please ignore the condition these sketches are in. Personally, I’m amazed they still exist — for a variety of reasons.

They do not exist because they are “great works of art.” I’ve yet to make any great work of art — I just make art. Aesthetic judgments about my work are for someone else and the best I can do is tell you I am so rarely “satisfied” by anything I make, I rarely show any of it to anyone. And when I do show my work, the generally underwhelming response is no surprise. I didn’t make whatever I did for that audience, apparently.

They - these drawings - do exist because I made so many of the things, self-portraits in particular. No, I’m not obsessed with myself. I picked up the habit in college. Each week we had to produce a self-portrait in a drawing class, present it on Friday, and discuss whether we’d progressed or not and so on. We did this because, as an artist, as long as you have a mirror, you also have a model. Also, we studied Rembrandt’s various self-portraits in paint and pen and etching… whether they were really self-portraits or him portraying a persona, a character, like an actor in a play.

Plus, no matter how I portrayed my image, I wasn’t apt to complain at myself for the lack of flattery or even the presence of it. So, ultimately, I daily made at least one quick sketch of myself, if nothing else; others took hours or days. Each had their own purpose, such as exploring a technique or as a study for some larger work I rarely made.

The 1986 charcoal sketch - the one in black and whites, high contrast, expressionistic; that one was for a woodcut or linoleum cut I never made. But I did keep the sketch and used a thumbtack to hang it on a wall in my superheated attic apartment in Athens, Georgia the year I transferred to the University to Georgia. It was a rough year, to say the least, but after two years at college in Dahlonega, I did manage to transfer out of that town and saw this as my first step towards going… somewhere else. Being an artist Somewhere Else, finally.

But I had no friends there. No supports. I didn’t know anyone and it’s a very large school. I went there hoping to find an artistic community, like-minded art students with whom to work and discuss ideas and theories. I was an idiot.

UGA is a music school, as far as the arts go. By this I mean, if you don’t already know, the university was, at that time, known for musical groups that went on to become regionally or even internationally famous. The B-52s had hit big just a few years before I arrived there; REM had done so even more recently. The Indigo Girls were playing around town as unknowns when I arrived and other really good acts came through the various bars and stages daily, certainly on weekends.

The 40 Watt Club was the place to be long before REM bought it out of nostalgia or whatever.

Some of those acts started in the UGA art department. I believe the B-52s and REM both did, so when I showed up all wide-eyed, escaping from a small town and small minds, imagine my surprise to find most of the “art students” were actually wanna-be musicians. At least on the side. Many people had bands, were trying to assemble groups, practiced a lot; some had gigs. It wouldn’t surprise me if I went to classes with a couple of folks who managed to get sucked into the music business machinery to become Big Stars.

What I got sucked into was a worsening depression.

It started when I moved to Athens in the boiling summer — it was too hot and humid to go out much in the daylight. When I did, I found downtown almost completely deserted — most students do not stick around for the summer and UGA is a significant part of the population of Athens, Georgia. I found a few folks and tried to strike up conversations: an atheist who’d lost the use of his legs in a car accident was sitting at a card table with pamphlets assaulting any sort of belief in G-d. So I talked with him, just to hear what he said. I’m unsure why he was doing what he was doing other than, in the days before the internet, it wasn’t all that easy to start an argument about ideas on a street corner and he, apparently, was bored.

He drew the attention of a couple of other guys, one of whom seemed OK at first, but who now I can say with some assurance was manic. He suffered from Bipolar Disorder and was delusional. He believed he’d grown up next door to Barbra Eden (of “I Dream of Jeanie” fame) — and initially, I bought it. I mean, it was not impossible.

He claimed his father was the actor who played Officer Andy Renko (Charles Haid) on “Hill Street Blues,” one of my favorite TV shows. From there the more, and more rapidly he spoke, the less I believed him. I was walking with him and the other guy who’d shown up with him - who never spoke - and the Talkin’ Dude was wandering all over downtown; then I figured out he was only going where I went - if I stopped, he stopped; if I walked, he walked. And he never stopped talking. The guy was stuck to me like flypaper.

It was the No-Talking Dude that concerned me. What was he up to? Was one guy the distraction and this guy the one who pulls the pistol and robs you? Or whatever? I excused myself and said I had an appointment at the college in the opposite direction but said I’d be back in fifteen minutes. Then I went and found my car, went home, and didn’t go back downtown for weeks. That was the end of going and trying to find some “friends” or even strike up conversations.

That was June or July. Time passed. Everything for me got darker and dimmer. I had a job at a food mart with a beer store and gas pumps — like 8 gas pumps and no cameras in the days before debit cards and in the days before pre-paid gas was a policy. Someone pulled a drive off on me one night and someone else passed a bad check on me, so I lost that job after a few weeks.

I wound up living on about $25.00 a week in 1986, which was just as low as it sounds now. I walked everywhere or caught the bus. I stopped eating - I just wasn’t hungry. Once every couple of days I’d buy a can of sardines and a package of no name spaghetti noodles - the noodles would last a few days, but not the sardines. I smoked filterless Pall Malls at an appalling rate, which helped further kill hunger, and drank black coffee constantly - plenty of places to get coffee and free refills in town.

My mind was dulled down. My interest in anything was nearly gone. I dropped from being about 160 pounds at 6 foot tall to 140 pounds and dropping until one of my friends decided to come visit, saw me, immediately took me to the store, bought some eggs and made me eat.

20 years old in 1986. Something about that drawing is, while not a realistic portrait of me, remains an accurate portrait of my soul, of how I felt as all that mess from ten years earlier, 1976 - before and after, plus all the insanity and disappointment I’d just walked away from in Dahlonega fell on me like a ton of lead. Though, I only understand that in retrospect: at the time, I couldn’t have articulated what was wrong, really, other than I believed I was worthless, a bad artist, and simply no damn good… all incorrect.

Welcome to the machine, minus the big star, steak bar, mean guitars, and Jaguars. It’s something that would come and go, as a feeling - or lack of feeling - but increasingly it remained — “it” being severe depression. I needed therapy, medication, and probably hospitalization. None of that would happen for 10 more years, unfortunately.

IV.

November 1988. Look at that “portrait.” Physically, it’s inaccurate - I was exaggerating features for effect and practicing pencil work on that portrait. The hair was about right so far as thickness went and my eyes, I’m afraid, had that sort of glare sometimes. It’s anger and defiance.

I transferred one more time, from Athens to Atlanta, Georgia and Georgia State University. Had I intended to get my MFA and teach art in a college, I should have stayed at UGA because, after 1986, I started making friends, feeling better; I had professors take an interest in me. I worked like a dog and enjoyed it again. But circumstances demanded I go to Atlanta because, having not yet learned much, I decided to get married and check off one of those predetermined boxes that my culture defined as “success.” “It's all right, we told you what to dream.” My would-be bride lived in Atlanta and would not live in Athens, so off to Atlanta I went.

I’ve written about my experiences in the GSU art department here:

JAILBREAK!

“Untitled [Cheap-Shot Attention Grabbing Angst-Ridden Horror Concerning Detention, Intention, and Pretention]” 1987, Richard Van Ingram, India ink, brush, watercolor on Arches BFK, about 20” x 30”

So I don’t think anything will be gained rehashing any of that other than to say, I should have stayed in Athens and been done with the BFA in 1988 and MFA by 1990, looking for jobs as a professor.

Instead, I walked into a damn mess in the printmaking section of the art department, was liked perfectly well in the Philosophy Department, wound up taking a left turn at Albuquerque, graduated with a BFA in 1991, received an MA in Philosophy in 1993, and went back to UGA to get a PhD in Philosophy I never finished due to everything coming to pieces, including me, in 1995. Leaving me - wait for it! - stuck back in Dahlonega, Georgia to start all over again until 2009.

”And you run, and you run

To catch up with the sun, but it's sinking

And racing around

To come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way

But you're older

Shorter of breath

And one day closer to death”

from TIME

Pink Floyd

DARK SIDE OF THE MOON (1973)

There’s me, November 1988 drawing that self-portrait. It’s the same guy who drew the other one two years earlier, almost to the day. Internally, is he any better off than previously, though one might look at the art and think so? No. Worse. He’s losing himself in the stress and panic. He just started all over again for a third time and really wasn’t prepared for the unnecessary hell he just walked into in 1987 at GSU. It’s been going on for a year; it’ll go on for three more. His life at home isn’t great, either, but he’s trying to make things work — he doesn’t give up easily.

And that’s what the picture shows: the guy who doesn’t give up easily, maybe a sort of imitation of the face of Michaelangelo’s “David,” except that isn’t the mask of confidence. It’s in some part rage and confusion and pain. Determination, sure, but a lot of regret that he has to be so damned determined at that point in life.

The demand for determination, by the way, will never end for him. Others, maybe; not him. That is his fate, his circumstance. Underdogs don’t get to assume victory or even finishing alive, literally or metaphorically. That guy in the drawing damn near died in 1995, seven years later.

He damn near died a few years ago, now due to his physical health.

And so it goes.

There’s nothing special or exceptional in that tale. We all suffer, we all have things that lay us low. And then we either get back up if we can or that’s the end of us. We imagine we have work to do, are needed by other people, needed by G-d to do whatever we were sent for, to create some meaning here in this hateful universe… or just stop or destroy things or become consumed with rage, or guilt, or hopelessness, or diseases.

There are no real predetermined, prechosen stations to tell you along your journey that you “succeeded.” That’s an illusion. What there is, along this road, is learning to drive well, to help others, to perform at a certain level of intensity and effort — this is a performative goal, not a “final goal,” a terminal goal, the sort most people think about when considering standards of success.3

Life is not like driving to Chicago. Chicago would be a final or terminal goal: we can get a map to show us how to get there, we drive the route, and in the end we’re in Chicago. We know we succeeded because we have attained our destination: Chicago. We’re done now and can rest.

That is not an adequate analogy for a human life.

No, life is simply like driving on a road. We don’t know where it goes, if anywhere, so its destination isn’t important — it’s a by-product, not the point of the drive. What is important is learning to deal with the obstacles on the road, other people and how they act on the road, not racing and competing (Why compete? Where are you going that others aren’t going as well?), but helping and giving a good example where possible. One builds skills over time, even shares the skills and teaches others how to drive better. One learns to enjoy the changing scenery, the other people, the challenges of the day. And then one simply faces the weather, the conditions, and the road at the highest level of intensity and effort one can manage until one dies.

Those skills for living well (“driving”) can be called virtues or moral values. You have to live up to them or make them present in your life by doing them at the right moments and doing them increasingly well until conditions prevent you from doing so. The skills for recognizing and appreciating the reality, the goodness, and the beauty of the world as you pass through are also essential for being good at travelling through this world.

Maybe you also make maps and leave some warnings about dangerous areas as well. Maybe they’re poems or songs, essays, or drawings.

Maybe.

28 December 2024

Gershom

Richard Van Ingram

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="

title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Only within the past year, at the age of 58, have I managed to cobble together a more accurate chronology of events than the one I believed previously. What I experienced for years up to 1977 and beyond was traumatic; my memory of how long events were is at times compressed, at times elongated. Episodes with months between them or weeks have been converted into one long episode in my mind. What isn’t inaccurate is the order of the events, their severity, or their reality. This note is added only as a commentary on how long it has taken, with an uncooperative parent and secretive relatives, to fix down this much personal history of which this scene is one small part.

Nothing of what I just wrote deserves your pity. I don’t want anyone’s pity — at age 10, maybe, but now, no. I’m simply sharing how things can be from the inside for a person who struggles with life. There is no way to get through life without suffering: the question is, how are you going to face the suffering? Are you going to pointlessly run from it or are you going to do your damnedest to push through, to imagine a life once the suffering passes and work towards that? Will you build and hold onto a meaningful dream or dissolve in the acid of a world turned hateful for some period of time? One of these, to live for the meaningful dream, is in your power; the other is simply a surrender that allows the world to easily maim and murder you.

I learned the distinction between terminal and performative goals reading a book by philosopher Mortimer J. Adler in the 1980s. I couldn’t tell you which. This revelation plays a major role in my own neo-Stoic approach to ethics (a.k.a. life, truth, goodness, beauty), but I owe Adler a great debt of thanks for this insight - among others.